Who Tells Your Story?

[caption id="attachment_1640" align="alignleft" width="201"] mnu.edu[/caption]

mnu.edu[/caption]

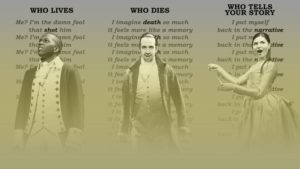

“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” – Hamilton: An American Musical

The best movie I’ve seen in a long time is Hidden Figures, the story of the African-American female mathematicians who helped NASA put men in space. I’m old enough to remember the Mercury astronauts and when a space launch was reason to gather your family around the TV. Everyone we ever saw in the NASA control rooms was a white man. So when the movie – and book by Margot Lee Shetterly – were released, the most common reaction was “I never knew that.” The second most common reaction was “Why haven’t we heard this story before?”

Hidden Figures is not the first book or film to tell a little known story. Sometimes it’s the telling of a story for the first time (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks). Sometimes it’s the story of a person who’s always been in the background (Hamilton: An American Musical). Why are we just now hearing about them decades or even centuries after the fact?

There have been a number of documentaries and books released in the past few years that address the AIDS epidemic. David France recently released his remarkable book based on the 2012 documentary, How to Survive a Plague. Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora is receiving much deserved praise. Two deeply emotional documentaries – Cecilia Aldorando’s Memories of a Penitent Heart and Erin Brethauer and Timothy Hussin’s Last Men Standing – came out last year. All are exhaustively researched, impeccably presented, critically acclaimed.

But why are they – and my next book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community – necessary? Do we really need all these books and films about the same thing?

I wondered the same thing when I was wavering on committing to this book. We’ve come to a point, in the fourth decade of the epidemic, when more memoirs and documentaries are focusing on the AIDS community. Some address the issues facing long-term survivors; others remind us of the obstacles we faced in those dark early days. But each and every one told a familiar story from a different angle. Each introduced us to people and events that were previously forgotten, or known only to a few. Each challenged you to look at the epidemic with fresh eyes.

That’s what I hope my book will do. It’s a huge responsibility, no doubt about it, to honor the contributions of straight women largely ignored in the above examples. There are so many stories that need to be told, like the origin of “Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It”. Or what happened when Elizabeth Taylor testified before Congress. Or why Ruth Coker Burks is called the “cemetery angel”.

The point I’m trying to make is not about my book, or the AIDS community. It’s about stories.

If all we ever hear is one version of a story, no matter how broad, it’s going to miss someone. Sometimes that omission is deliberate, to suppress voices that threaten the official version and don’t further its agenda. And sometimes the omission is of something or someone that was simply deemed unimportant.

That’s when the Rebecca Skloots and Margot Lee Shetterlys of the world step up, uncovering the story of Henrietta Lacks and the injustice that was largely unknown even to her own family; revealing the unrecognized twin barriers of racism and sexism within NASA at a time when the country was united behind the space race.

I’m not comparing myself to them. All I’m saying is don’t assume that any story – no matter how sweeping – is the only one. Sometimes the people involved can tell the stories. Sometimes it takes a stranger, stumbling on a tidbit of information that surprises and intrigues them.

And if you don’t tell them, who will?

mnu.edu[/caption]

mnu.edu[/caption]“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” – Hamilton: An American Musical

The best movie I’ve seen in a long time is Hidden Figures, the story of the African-American female mathematicians who helped NASA put men in space. I’m old enough to remember the Mercury astronauts and when a space launch was reason to gather your family around the TV. Everyone we ever saw in the NASA control rooms was a white man. So when the movie – and book by Margot Lee Shetterly – were released, the most common reaction was “I never knew that.” The second most common reaction was “Why haven’t we heard this story before?”

Hidden Figures is not the first book or film to tell a little known story. Sometimes it’s the telling of a story for the first time (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks). Sometimes it’s the story of a person who’s always been in the background (Hamilton: An American Musical). Why are we just now hearing about them decades or even centuries after the fact?

There have been a number of documentaries and books released in the past few years that address the AIDS epidemic. David France recently released his remarkable book based on the 2012 documentary, How to Survive a Plague. Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora is receiving much deserved praise. Two deeply emotional documentaries – Cecilia Aldorando’s Memories of a Penitent Heart and Erin Brethauer and Timothy Hussin’s Last Men Standing – came out last year. All are exhaustively researched, impeccably presented, critically acclaimed.

But why are they – and my next book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community – necessary? Do we really need all these books and films about the same thing?

I wondered the same thing when I was wavering on committing to this book. We’ve come to a point, in the fourth decade of the epidemic, when more memoirs and documentaries are focusing on the AIDS community. Some address the issues facing long-term survivors; others remind us of the obstacles we faced in those dark early days. But each and every one told a familiar story from a different angle. Each introduced us to people and events that were previously forgotten, or known only to a few. Each challenged you to look at the epidemic with fresh eyes.

That’s what I hope my book will do. It’s a huge responsibility, no doubt about it, to honor the contributions of straight women largely ignored in the above examples. There are so many stories that need to be told, like the origin of “Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It”. Or what happened when Elizabeth Taylor testified before Congress. Or why Ruth Coker Burks is called the “cemetery angel”.

The point I’m trying to make is not about my book, or the AIDS community. It’s about stories.

If all we ever hear is one version of a story, no matter how broad, it’s going to miss someone. Sometimes that omission is deliberate, to suppress voices that threaten the official version and don’t further its agenda. And sometimes the omission is of something or someone that was simply deemed unimportant.

That’s when the Rebecca Skloots and Margot Lee Shetterlys of the world step up, uncovering the story of Henrietta Lacks and the injustice that was largely unknown even to her own family; revealing the unrecognized twin barriers of racism and sexism within NASA at a time when the country was united behind the space race.

I’m not comparing myself to them. All I’m saying is don’t assume that any story – no matter how sweeping – is the only one. Sometimes the people involved can tell the stories. Sometimes it takes a stranger, stumbling on a tidbit of information that surprises and intrigues them.

And if you don’t tell them, who will?