When Friend Grief Hits Home

There have been a lot of important stories in the news lately. So it was easy to miss a small story in late July.

There have been a lot of important stories in the news lately. So it was easy to miss a small story in late July.Betsy Ebeling was a suburban Chicago woman whose death was noted because of who her best friend was: Hillary Rodham Clinton. Though the obituary made clear that she was loved and admired by everyone who met her, the friendship that began in 6th grade was the one that defined her in the public eye.

A few hours after this story broke, while I was making dinner, my phone chimed with an incoming text message. It was from one of my oldest and dearest friends. The text was about his health and was not good news.

The details are not ones that I would share publicly, and though I assured him with a rational response that he had no need to panic, inside I was crying. He was not my best friend, but one of a small group of very close friends.

I was in high school the first time a friend died, killed a week after he landed in Vietnam. There have been many more since then: classmates, my parents’ friends, people I worked with, neighbors, parents of my daughter’s friends. It doesn’t get easier. It shouldn’t.

Some of my closest friends - at my insistence - keep me up to date on their health. That insistence was rooted in my experiences in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Those were the days when every issue of the weekly LGBT newspaper contained the shocking announcement of someone’s death. It was often someone you didn’t know was sick, only that you hadn’t seen them for a while. Even now, if I lose touch with a friend I assume they’re dead or dying. Paranoia strikes deep, as Stephen Stills sang so long ago.

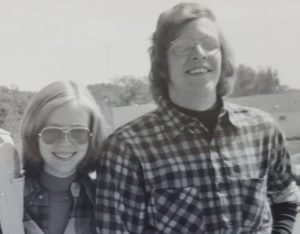

The friend whose text interrupted my dinner preparations died three weeks ago. During those intervening weeks, we spoke and texted even more often than usual. The news he’d shared was serious, but not life-threatening. He was preparing for a surgical procedure that would dramatically improve his quality of life, but it never happened. David died rather suddenly and I was not prepared.

My grief has gutted me in a way that I haven’t experienced since the death of my parents. A 46-year friendship - a complicated, sometimes infuriating, but often fun friendship - cannot be easily forgotten. The photo is us in 1974, the year after we met, when we were both dancing in a U of Iowa production of Fiddler on the Roof. As I sometimes joked, we’d been friends since Nixon was president. A long time. Just not long enough.

I’m bracing myself for his memorial service in two weeks. And though there are questions that will probably never be answered, I am grateful for one thing: there was nothing important left unsaid. We told each other “I love you” at the end of every phone call and most text conversations. We acknowledged how important we were to each other, though he was more vocal than I was. At least I don’t feel guilty about not telling him.

If you too are blessed with friends who make your life meaningful, the thought of losing them is probably something you avoid. That kind of loss can change your life, as so many of the people I interviewed for my Friend Grief books proved.

So, what to do? Maybe you should just do what James Taylor sang: “shower the people you love with love”.

Tell them.

Show them.

Treasure them.