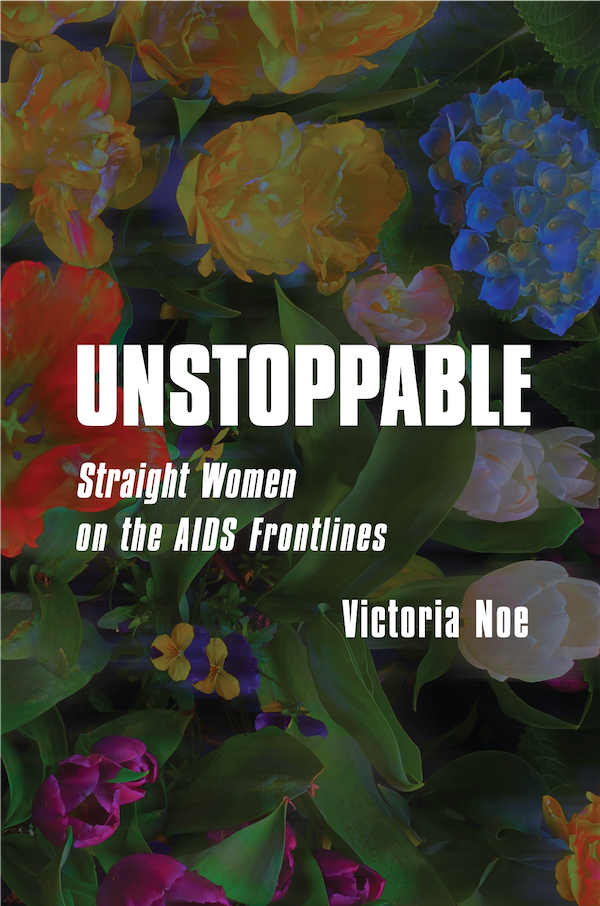

Men Need a Language to Grieve

Apr 12, 2016 by Victoria Noe, in bereavement

, Friend Grief and Men: Defying Stereotypes

, Grief

, grieving styles

, men's grief

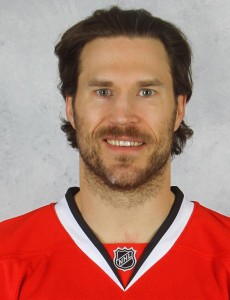

[caption id="attachment_1131" align="alignleft" width="158"] The late Steve Montador, whose suicide inspired his friend.[/caption]

The late Steve Montador, whose suicide inspired his friend.[/caption]

In her book, When Men Grieve: Why Men Grieve Differently & How You Can Help, Dr. Elizabeth Levang suggests that men lack a language for grief. Literally.

I’m old enough to remember when Jackie Kennedy was criticized for not crying in public after her husband’s assassination. Women are expected to cry, wail, talk about their loss. She didn’t, and her behavior was looked at as unfeeling. That she was recuperating from the trauma of seeing her husband shot dead in front of her was not necessarily a good excuse. Her insistence on soldiering on, keeping commitments, and doing everything with remarkable self-control and grace was not the type of behavior expected in women. It was, however, what we expect from men.

In the course of writing the Friend Grief books, I’ve read about and interviewed men who were caught in that sexist expectation. Some, as they wiped away tears, admitted they’d never told anyone before what they’d just told me about the profound grief they felt for their friends. They hadn’t shared because no one understood or was willing to listen.

I assumed early on that having a master’s degree in speech and dramatic art rather than psychology would be a disadvantage. I was wrong. It turned out to be a huge asset. I wasn’t interviewing people to pass judgment or diagnose or prescribe. I was there to listen. And men need someone to listen to them when they grieve.

They need someone who won’t insist that they behave a certain way or fulfill specific expectations.

Men are just as confused, angry and distraught as women when a friend dies. And they deserve the freedom to feel that way: not just when they’re alone, but with others willing to listen.

It doesn't mean they don't want to take charge or "do" something. Daniel Carcillo, on his retirement from the Chicago Blackhawks, started a charity in memory of his friend, Steve Montador. It's more than that: it's the need to grieve in whatever way feels right. Who wouldn't want that?

One of the men in the next book admitted, “I think I’ll have a harder time with (my best friend)’s death than with my own.” Men’s friendships are deep and wide and crucial to their journey to understand what it means to be a man.

It’s time we all acknowledge that, and give men the opportunity to grieve their friends as they see fit.

Would you like a free e-book of Friend Grief and Men: Defying Stereotypes? Just sign up for my email newsletter in the upper right hand corner of this page.

The late Steve Montador, whose suicide inspired his friend.[/caption]

The late Steve Montador, whose suicide inspired his friend.[/caption]In her book, When Men Grieve: Why Men Grieve Differently & How You Can Help, Dr. Elizabeth Levang suggests that men lack a language for grief. Literally.

I’m old enough to remember when Jackie Kennedy was criticized for not crying in public after her husband’s assassination. Women are expected to cry, wail, talk about their loss. She didn’t, and her behavior was looked at as unfeeling. That she was recuperating from the trauma of seeing her husband shot dead in front of her was not necessarily a good excuse. Her insistence on soldiering on, keeping commitments, and doing everything with remarkable self-control and grace was not the type of behavior expected in women. It was, however, what we expect from men.

In the course of writing the Friend Grief books, I’ve read about and interviewed men who were caught in that sexist expectation. Some, as they wiped away tears, admitted they’d never told anyone before what they’d just told me about the profound grief they felt for their friends. They hadn’t shared because no one understood or was willing to listen.

I assumed early on that having a master’s degree in speech and dramatic art rather than psychology would be a disadvantage. I was wrong. It turned out to be a huge asset. I wasn’t interviewing people to pass judgment or diagnose or prescribe. I was there to listen. And men need someone to listen to them when they grieve.

They need someone who won’t insist that they behave a certain way or fulfill specific expectations.

Men are just as confused, angry and distraught as women when a friend dies. And they deserve the freedom to feel that way: not just when they’re alone, but with others willing to listen.

It doesn't mean they don't want to take charge or "do" something. Daniel Carcillo, on his retirement from the Chicago Blackhawks, started a charity in memory of his friend, Steve Montador. It's more than that: it's the need to grieve in whatever way feels right. Who wouldn't want that?

One of the men in the next book admitted, “I think I’ll have a harder time with (my best friend)’s death than with my own.” Men’s friendships are deep and wide and crucial to their journey to understand what it means to be a man.

It’s time we all acknowledge that, and give men the opportunity to grieve their friends as they see fit.

Would you like a free e-book of Friend Grief and Men: Defying Stereotypes? Just sign up for my email newsletter in the upper right hand corner of this page.