Remembering the Dead, One Name at a Time

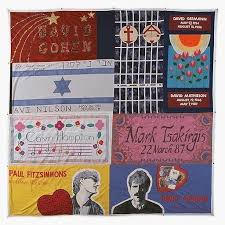

I was watching Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt the other day. The documentary was made in 1989, when the Quilt was fairly new. It was still small enough - small being a relative term - to be fully displayed on the National Mall. Now the Quilt contains over 48,000 panels, each measuring exactly 3’x6’.

I was watching Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt the other day. The documentary was made in 1989, when the Quilt was fairly new. It was still small enough - small being a relative term - to be fully displayed on the National Mall. Now the Quilt contains over 48,000 panels, each measuring exactly 3’x6’.I moved on to a newspaper interview with a woman who helped make her son’s panel. She remarked that every panel, every name, represented not just someone who died from AIDS, but all the people who loved them. That’s true of other memorials.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, also in Washington, was controversial when the design was first unveiled. A 21 year old woman, Maya Lin, daughter of Chinese immigrants, designed it (not a man, not a veteran) and many were determined to hate it from the beginning. The nicest response I remember hearing was that it was depressing instead of uplifting like other, more traditional memorials.

Then the memorial opened and though there were still those who demanded - and got - representational statues added to the area, most everyone else was amazed by the power of what they saw: 58,148 names, every American who died in that war, etched into a stark, black wall.

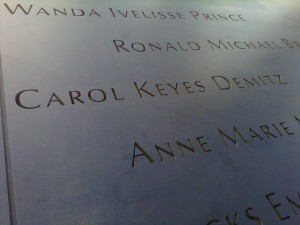

Then the memorial opened and though there were still those who demanded - and got - representational statues added to the area, most everyone else was amazed by the power of what they saw: 58,148 names, every American who died in that war, etched into a stark, black wall.The 9/11 Memorial in New York City also lists the names of all those who died that day (as well as those who died in the World Trade Center bombing in 1993) on the footprints of the twin towers.

All three memorials - two fixed in place, one too large to display in its entirety - are largely comprised of names. All, like that mother said, are reminders of the friends and family members left behind.

It seems normal now, to build a memorial to a battle or terrorist attack or even a natural disaster with the names of those lost. It wasn’t always like that. Inspiring, towering sculptures meant to evoke determination, patriotism and optimism were what we came to expect.

The Vietnam Memorial (the “Wall”) lists the dead in chronological order. That’s it: no service branch, no location, no age, no hometown. Just the names. You have to check the kiosk or go online to find out more.

During the years of heated debate over the 9/11 Memorial, designs listing the names of those lost were highly favored. But how to list them became a contentious discussion. The Families Association finally won: the names are listed in what is now called a “relational” way. Some sections of the Memorial make that clear by indicating why those names are together: Port Authority officers, airplane passengers and crew, FDNY ladder and truck houses. Most of the names do not. So they are listed with their coworkers in the Twin Towers. That means everyone who worked for, say, Cantor Fitzgerald is grouped together. Efforts were even made to put best friends close to each other.

During the years of heated debate over the 9/11 Memorial, designs listing the names of those lost were highly favored. But how to list them became a contentious discussion. The Families Association finally won: the names are listed in what is now called a “relational” way. Some sections of the Memorial make that clear by indicating why those names are together: Port Authority officers, airplane passengers and crew, FDNY ladder and truck houses. Most of the names do not. So they are listed with their coworkers in the Twin Towers. That means everyone who worked for, say, Cantor Fitzgerald is grouped together. Efforts were even made to put best friends close to each other.The AIDS Quilt is a bit more problematic. They’ve accepted panels for thirty years now and it’s not always possible to position friends and lovers close to each other. That’s because each panel is sewn together into a group of eight to make a square that measures 12’x12’. I found out I guy I knew from college died from AIDS when I saw his panel on the cover of the first book about the Quilt. But it was years later when I found out the significance of the placement: his panel is next to his lover’s (the bottom two in the photo above).

I keep thinking about that woman’s comment, that each name represents more than just that person. It’s certainly true for me. I know people whose names are displayed on all three of these memorials: one at 9/11, two on The Wall, God only knows how many on the Quilt. And I’m not the only person who remembers them.

These memorials are their own cemeteries, a place to visit, especially for those who had no body to bury. They are a way of ensuring that these people are not forgotten.

If you have a chance to visit the memorials in Washington and New York, or catch a display of a small section of the Quilt, do it. Most of the people there will have no personal connection to the names on view. But some will. They’re the ones who crouch down in front of a panel, or run their fingers over the engraved names. They’re grieving and remembering and celebrating, all at the same time. That’s the power of these tributes, a power that will last long after anyone remembers the lives behind those names.